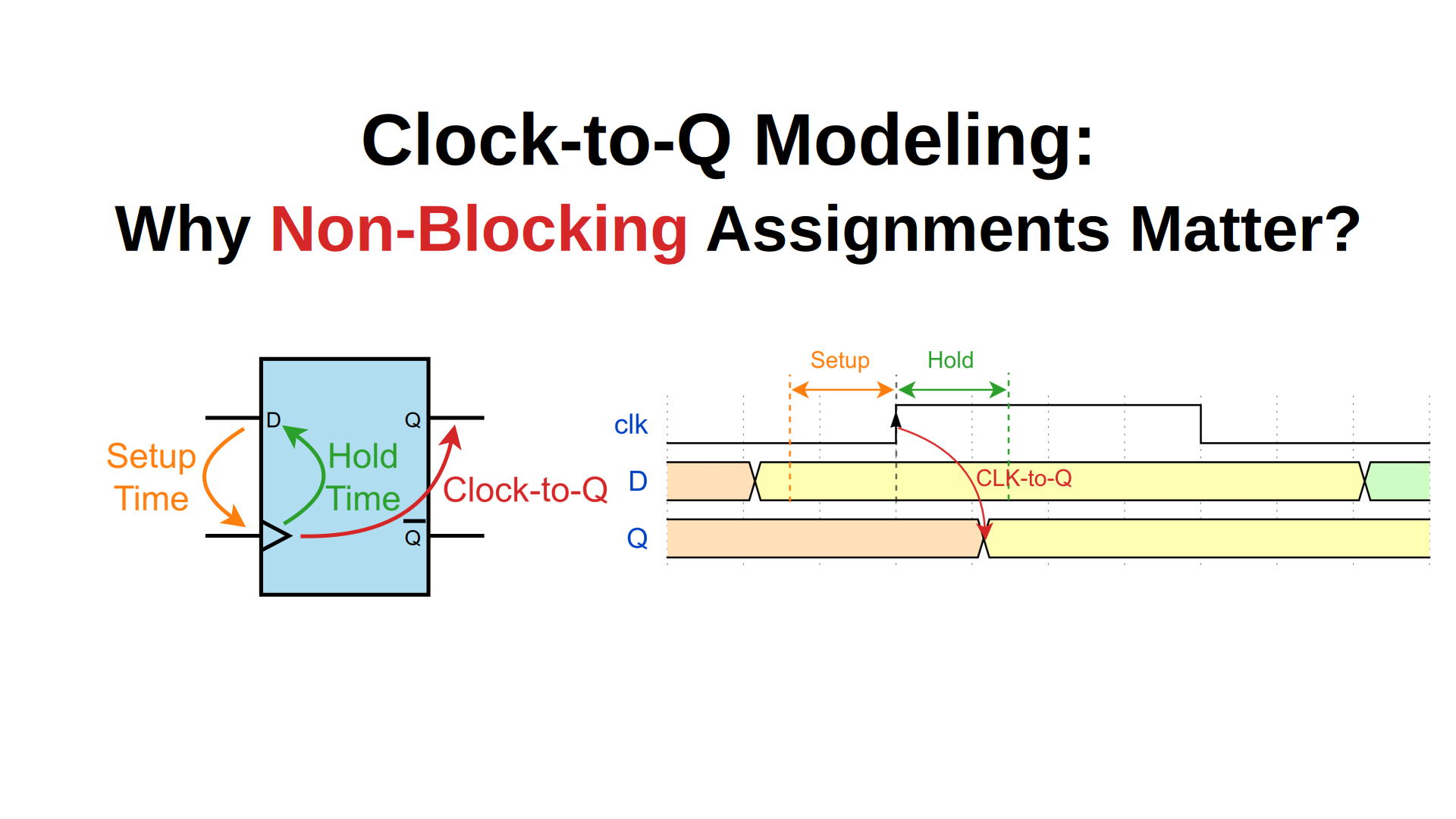

SV15. SystemVerilog Clock-to-Q Modeling: Why Non-Blocking Assignments Matter

Video Tutorial

Watch this comprehensive video explanation of Modeling Clock-to-Q Delay in SystemVerilog:

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Understanding Flip-Flop Timing Parameters

- The RTL Simulation Challenge

- Clock-to-Q Delay in Practice

- SystemVerilog Solution: Non-Blocking Assignments

- Implementation Example

- Best Practices

- Common Pitfalls

Introduction

When designing digital circuits with flip-flops, understanding and properly modeling timing parameters is crucial for creating synthesizable and functionally correct SystemVerilog code. This guide focuses on one of the most important timing parameters: Clock-to-Q delay and how to model it effectively in RTL design.

Understanding Flip-Flop Timing Parameters

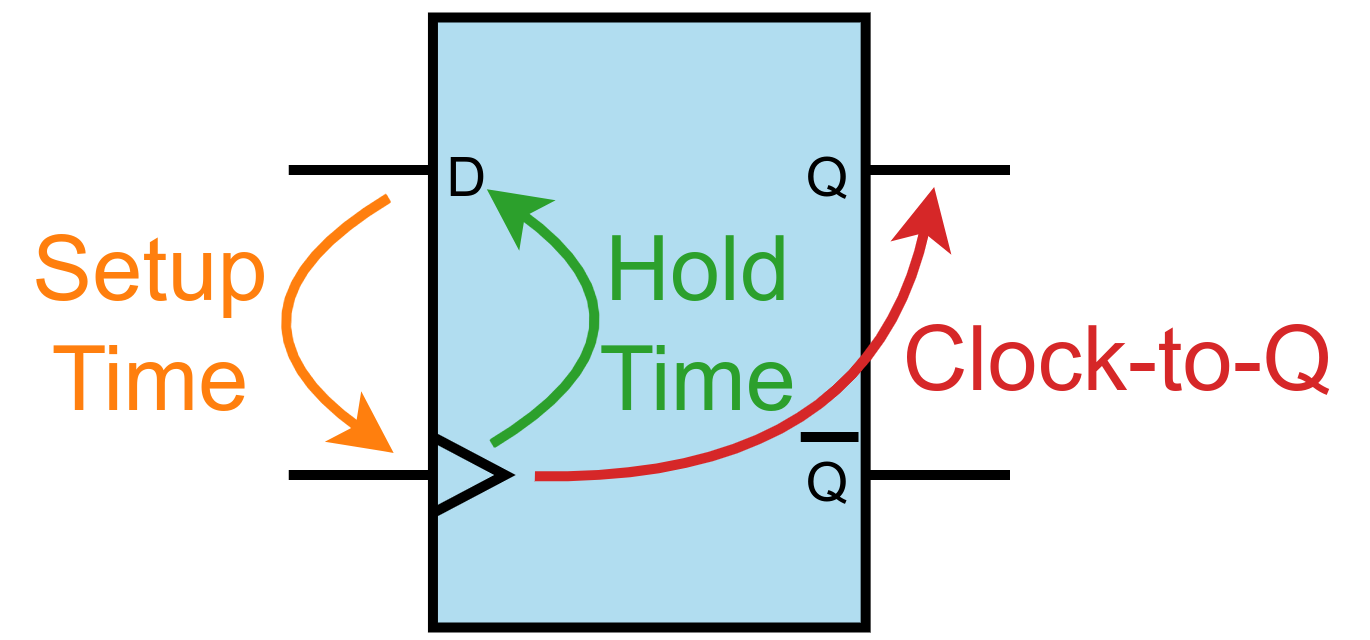

Flip-flops are fundamental building blocks of sequential digital circuits, and they have three critical timing parameters:

Setup Time

The minimum time duration that input data must be stable before the active clock edge. Violating setup time can cause metastability or incorrect data capture.

Hold Time

The minimum time duration that input data must remain stable after the active clock edge. Hold time violations can also lead to metastability.

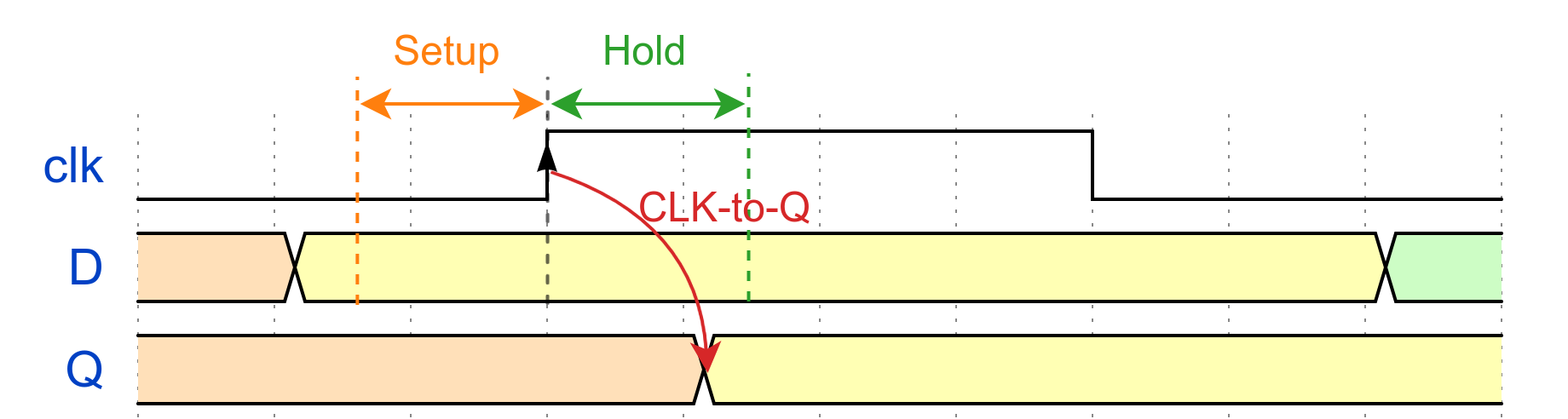

Clock-to-Q Delay

The propagation delay from the active clock edge until the output reflects the new value.

The RTL Simulation Challenge

RTL (Register Transfer Level) modeling presents a fundamental challenge when it comes to timing:

Zero Simulation Time Abstraction

- RTL models operate in zero simulation time

- Timing parameters like setup, hold, and Clock-to-Q delays are abstracted away

- This abstraction simplifies simulation but can hide critical timing dependencies

The Instantaneous Update Problem

Without proper Clock-to-Q delay modeling:

- Flip-flop outputs change immediately after the clock edge

- Cascaded flip-flops show unrealistic instantaneous signal propagation

- Certain circuit behaviors that depend on timing delays may not be accurately represented

Real Hardware vs. RTL Simulation

In physical hardware:

- Clock-to-Q delays are finite and measurable

- Previous output values remain available during the delay period

- These delays are essential for proper operation of certain circuit topologies

Clock-to-Q Delay in Practice

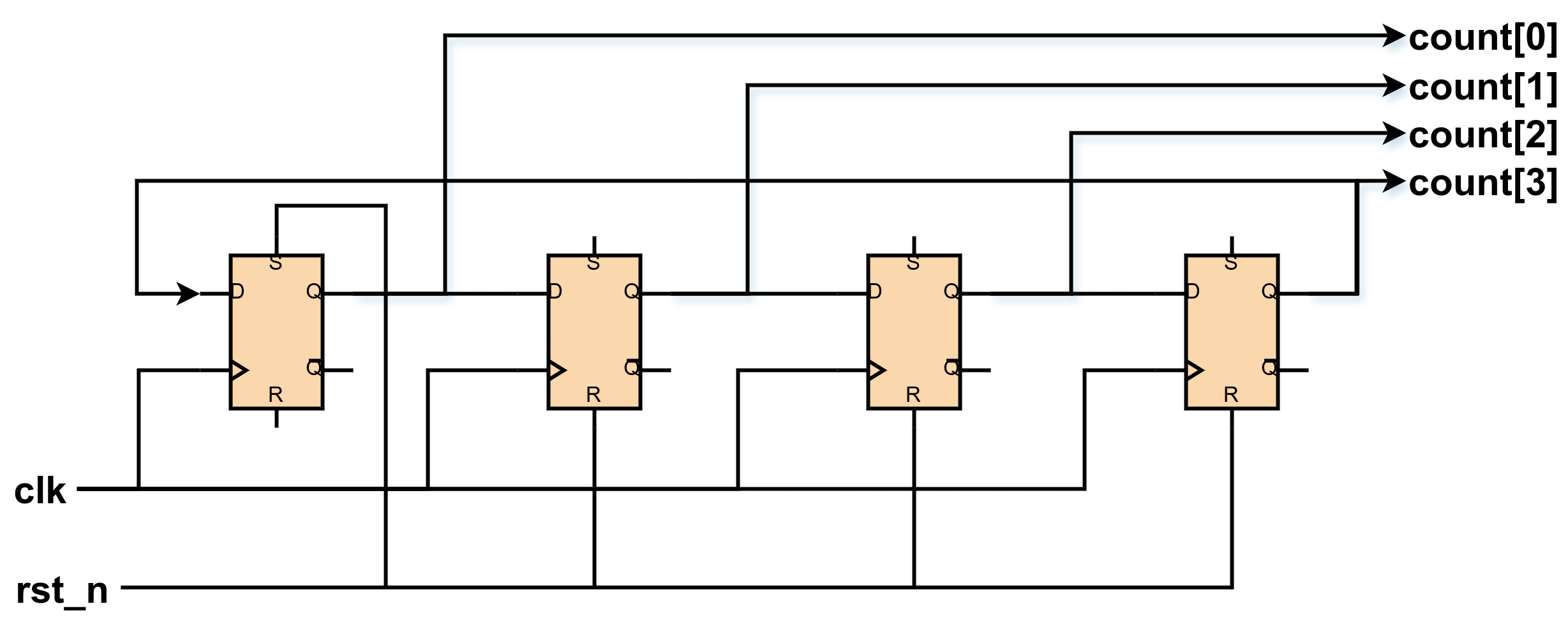

Ring Counter: A Perfect Example

A ring counter is an excellent case study for understanding why Clock-to-Q delay modeling matters:

Circuit Function:

- Shifts a single ‘1’ bit through a sequence of flip-flops

- Creates a rotating pattern:

4'b0001→4'b0010→4'b0100→4'b1000→4'b0001

Critical Timing Dependency:

Clock Cycle N: count = 4'b0001

↓ (Clock edge occurs)

Clock Cycle N+1: count = 4'b0010

Why Clock-to-Q Delay is Essential:

- At clock edge, all flip-flops simultaneously:

- Capture their input values (based on previous outputs)

- Begin transitioning their outputs (after $T_{clk2q}$ delay)

- During $T_{clk2q}$ delay, previous output values remain stable

- This stability window allows proper data transfer between flip-flops

Without Clock-to-Q Modeling:

- All flip-flops would update simultaneously in zero time

- The circuit would lose its shifting behavior

- Simulation results would not match hardware behavior

SystemVerilog Solution: Non-Blocking Assignments

SystemVerilog provides an elegant solution through the non-blocking assignment operator (<=):

Two-Phase Execution Model

Non-blocking assignments operate in two distinct phases:

1. Evaluation Phase

- All right-hand sides of

<=assignments are evaluated - Results are stored in temporary simulation variables

- No updates to left-hand sides occur yet

2. Update Phase

- All left-hand sides are updated simultaneously from temporary values

- This phase models the Clock-to-Q delay behavior

- Creates the illusion of simultaneous updates while preserving sequential logic

How It Models Clock-to-Q Delay

// At clock edge:

count[0] <= count[3]; // RHS evaluated: current count[3] value

count[1] <= count[0]; // RHS evaluated: current count[0] value

count[2] <= count[1]; // RHS evaluated: current count[1] value

count[3] <= count[2]; // RHS evaluated: current count[2] value

// All LHS updates happen simultaneously after evaluation

This two-phase model effectively captures the essence of Clock-to-Q delay without explicit timing simulation.

Implementation Example

Here’s a complete ring counter implementation demonstrating proper Clock-to-Q delay modeling:

module ring_counter #(

parameter WIDTH = 4

) (

input logic clk,

input logic rst_n,

output logic [WIDTH-1:0] count

);

always_ff @(posedge clk or negedge rst_n) begin

if (!rst_n) begin

// Initialize with single bit set

count <= {{WIDTH-1{1'b0}}, 1'b1};

end else begin

// Rotate the bits using non-blocking assignments

count[0] <= count[WIDTH-1]; // Feedback from MSB to LSB

for (int i = 1; i < WIDTH; i++) begin

count[i] <= count[i-1]; // Shift each bit

end

end

end

endmodule

Alternative Implementation (Explicit Assignment)

always_ff @(posedge clk or negedge rst_n) begin

if (!rst_n) begin

count <= 4'b0001;

end else begin

count[0] <= count[3]; // Feedback from last to first

count[1] <= count[0]; // Shift right

count[2] <= count[1]; // Shift right

count[3] <= count[2]; // Shift right

end

end

Best Practices

1. Always Use Non-Blocking Assignments for Sequential Logic

// Correct: Non-blocking assignment

always_ff @(posedge clk) begin

q <= d;

end

// Incorrect: Blocking assignment in sequential logic

always_ff @(posedge clk) begin

q = d; // Don't do this!

end

2. Separate Combinational and Sequential Logic

// Sequential logic (non-blocking)

always_ff @(posedge clk) begin

reg_out <= reg_in;

end

// Combinational logic (blocking)

always_comb begin

comb_out = input_a & input_b;

end

3. Use Consistent Clock Domains

// All flip-flops in same clock domain

always_ff @(posedge clk or negedge rst_n) begin

if (!rst_n) begin

stage1 <= '0;

stage2 <= '0;

stage3 <= '0;

end else begin

stage1 <= data_in;

stage2 <= stage1;

stage3 <= stage2;

end

end

Common Pitfalls

1. Mixing Blocking and Non-Blocking Assignments

// Don't mix assignment types in sequential logic

always_ff @(posedge clk) begin

temp = input_val; // Blocking - executes immediately

output_reg <= temp; // Non-blocking - scheduled for later

end

If you need a temporary variable inside the

always_ffblock, declare it inside the block so it has block-level scope:

always_ff @(posedge clk) begin

logic [WIDTH-1:0] temp; // Temporary variable

temp = input_val; // Blocking - executes immediately

output_reg <= temp; // Non-blocking - scheduled for later

end

2. Race Conditions with Blocking Assignments

// Problematic: Order-dependent behavior

always_ff @(posedge clk) begin

a = b; // Executes immediately

b = c; // Executes immediately - 'a' gets old 'b' value

end

// Correct: Order-independent behavior

always_ff @(posedge clk) begin

a <= b; // Scheduled for update

b <= c; // Scheduled for update - both use current values

end

Conclusion

Proper modeling of Clock-to-Q delay through non-blocking assignments is essential for creating synthesizable SystemVerilog code that accurately represents hardware behavior. By understanding the two-phase execution model and following established best practices, designers can create robust sequential circuits that work correctly in both simulation and hardware implementation.

The ring counter example demonstrates how this seemingly simple concept has profound implications for circuit functionality, making it a cornerstone of effective RTL design methodology.